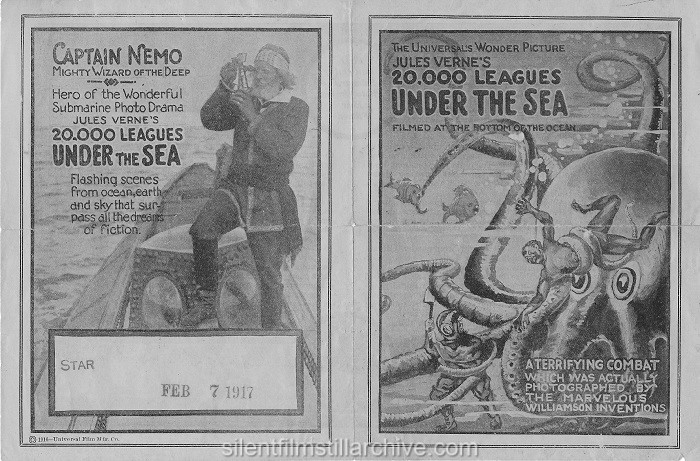

The solution it proposed gave, at least, full liberty to the imagination. It rallied round it a certain number of partisans. Fictional images, be they lithographs in children’s books or stills from popular sci-fi films, play an important part in this process.Was warmly discussed, which procured it a high reputation. Rather, they are a critical part of the process of developing science and technology they can inspire or, indeed, discourage researchers to turn what is thinkable into new technologies and they can frame the ways in which the ‘public’ reacts to scientific innovations. The paper aims to show that popular culture and imagination do not simply follow and reflect science. This paper examines the visual and verbal imagery surrounding the various ‘submarines’ that have travelled through popular imagination, from Jules Verne’s Nautilus, driven by Captain Nemo, up to the most iconic and most recent representation of nanotechnology, from the journey through the hidden space of the world’s oceans on board the hidden space of a luxurious submarine, to expeditions into the hidden space of the human body as portrayed in films such as Fantastic Voyage, Inner Space and beyond.

They continuously serve to sciencefictionalise science fact and blur the boundaries between cultural visions and scientific reality. Vehicular utopias, such as Jules Verne’s voyage under the sea, and dream machines, such as nanorobots, have tended to fill this surreal gap and have had an immediate and long lasting hold on public imagination. The view that nanotechnology will lead to tiny robotic submarines navigating our bloodstream is ubiquitous but there is an almost surreal gap between what the technology is believed to promise and what it actually delivers. This narrative form excludes females - a perfect analogy to the psyche of the pre-adolescent boy. Indeed, within the double claustrophobic enclosure of submarine and ocean, the interplay of the characters forms a complete mythos of filial (as opposed to familial) conflict and heroic quest. The power of the book derives partly from the ingenious ways in which Verne casts four principal male characters and portrays their homosocial relationships, and partly from Verne’s use of the imagery and symbolism of the ocean, representing both the repressed female and the savagery of Nature.

Despite truncated and inept translations, and indeed, despite the strictures imposed on Verne by his own publisher, this novel, and its dark hero, Captain Nemo, transcends genres and continues to be read by a wide audience of both juveniles and adults. Among all the books classed as “boys’ literature,” Jules Verne’s 1870 novel, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, maintains its position as one of the most-read and best-remembered adventure tales.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)